Alternative and off-grid housing communities in the UK

Contents |

[edit] What does off grid mean?

In the simplest sense of the term, off grid describes a house, building or community that is not connected to a national or regional electricity grid. The International Energy Agency suggests that off-grid systems are: ‘Stand-alone systems for individual households or groups of consumers’ (May 2021). Whilst the Canadian Green Building Council uses the term islanded grid to describe ‘A small electricity grid that is not connected to the provincial grid’ (March 2021), as might be used for a small community.

In the UK, it is not illegal to be off grid, though in some countries it is discouraged and in some cases considered illegal. In recent years may discussions around net zero buildings, the climate emergency, cost of living crisis, housing crisis and energy crisis have opened up the conversation around off grid communities.

The Cambridge dictionary describes two meanings, with the second extending further and not connected to any of the main utilities, intentionally or unintentionally, such as water and gas supply. As well as not using sewage and non-organic solid waste material infrastructures.

Off-grid might also be used in colloquial English, perhaps less specifically, to describe a person who has gone or moved away into nature or the countryside, implying getting away from the daily routines of modern life.

[edit] Alternative and temporary to permanent and mainstream

Historically many of these kinds of communities have been associated with alternative lifestyles, and counter cultures, however in recent years off-grid living has had somewhat of a resurgence. There are many different terms that may incorporate off grid systems and the communities that rely on them, including self-sufficient woodland communities, land-based communities, low impact communities, communes, sustainable smallholdings, eco villages, alternative communities, eco retreats etc. But these can vary widely in terms of their ideals, design, use of systems, management approach and level of self-sufficiency. Some are part of, or extensions of, existing estates (a consideration in terms of planning) whilst others, generally far less in number, exist independently in natural areas.

Importantly, many of the latter type of communities in the UK have in the eyes of the planning system been considered, in their various forms as temporary. Falling under and navigating various different elements of the planning system, from temporary planning, to permitted development, the caravan sites act, to planning policy for traveller sites, but generally not seen as a permanent solution for housing.

The popularity of these kinds of housing and living solutions in other contexts, from co-operative housing, community land-trusts, communal living to off-grid communities have in the past few years been reported as having a rise in popularity. From urban-edge communities (https://www.newstatesman.com/spotlight/2019/08/rise-co-living) to rural estates (https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-suffolk-64153693) and off-grid woodland communities (https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jul/03/the-rise-of-woodland-off-gridders-it-makes-more-sense-than-a-nine-to-five)

In April 2023, Tinkers Bubble, one of the UK's best known off-grid, alternative living, woodland communities, received permanent planning permission. This was an important milestone for a community that has existed for 30 years, 25 of which have been under temporary planning permission. It may also be considered an important milestone in the formal recognition and acceptance of these examples as possible solutions to a housing, energy, climate and biodiversity crisis.

[edit] Aspects to being off grid

There are numerous individual houses or buildings in the UK, often in rural settings, that are off grid due to circumstance or choice. For example the BBC reported in 2019 on Margaret Gallagher who had been living, Irish border in County Fermanagh, and off-grid for almost 80 years. Whilst there maybe many lesser known individual houses that function off grid, and whilst many communities aspire to be self-sufficient or net-zero few achieve this over the longer term.

There are however a number of communities in the UK who temporarily or permanently live off grid, often associated with a certain type of sustainable living, culture and indeed architecture.

[edit] Energy Independence

Whilst off-grid essentially means not being connected to the national grid electrical supply system, this means that any community or building without a connection but a need for electricity will need to, not only be able to produce its own electricity but also store it. Smaller communities are most likely to make use of electricity generated by renewable technology such as photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, or hydroelectric systems or in some cases smaller biomass plant systems, because of the infrastructure, cost and often carbon emissions associated with anything else. Micro-grids, along with battery systems might supply a number of different properties within the community or each individual dwelling, either way localised production and storage systems allow off grid communities access to electricity without connecting to the central regional or national power grid system.

[edit] Self-sufficient water-waste and supply

An off-grid or self sufficient water supply has to include means of collecting, storing, and most likely treatment of stream, lake or rainwater for human use. It is in many cases likely to also involve a dramatic reduction in the amount of water that is used by a community for washing, cleaning etc, than in an average urban context.

There are various options for water treatment systems, such as reed bed systems which can gradually purify waste water through a series of natural reed filtration lakes through to ultraviolet light filtration systems, though these are most likely to have higher energy use requirements. The principles of any self-sufficient water system is to reduce the amount of water used or ensure careful use, to reduce the level of contaminants and detergents used in cleaning, washing and so on, thus allowing the water to be more readily filtered and reused.

Finally, separation is usually a key element to self sufficient water use from separating solid waste from liquid waste sewerage through to the separation of different qualities of water for different uses, with lower grades for cleaning or irrigation and higher grades suitable to come in contact with residents and finally for drinking.

In combination these different aspects help water supply from different renewable sources meet the demands of a community and removes reliance of the public water supply system.

[edit] Waste Management

Waste management issues are likely to vary dramatically for different households, even within communities that are aware of issues surrounding waste. Solid organic waste material is most likely to be separated as part of the off grid sewage system and organic food waste organically composted, with the nutrients effectively recycled as part of an approach to land-use.

Other waste materials, are most likely to be reduced in comparison with average waste production per household because of reduced reliance on supermarkets and purchased goods. Recycling of waste materials is one common solution to dealing with non organic wast produced. However in order to remain truly off grid in terms of waste, such communities should no longer need to rely on municipal waste systems, be that waste collection or central dump sites. .

[edit] Aspects of autonomy

Whilst the concept of off-grid living often aligns with sustainability goals and reduced environmental impact, achieving autonomy in the process will most likely require management structures of some kind, or at least a social system that works within the community itself. This aspect of self-organisation being one that varies dramatically between communities, the people, as well as over time.

[edit] Examples of UK off-grid communities

Below are some examples of the most established UK communities that are considered to be off grid.

[edit] Tinkers Bubble

Tinkers Bubble is an off-grid settlement in Somerset. It is a small community that practices organic farming and forestry, and residents use renewable energy sources such as solar panels and wind turbines. The village aims to minimise its environmental impact and promote sustainable living.

Tinkers Bubble is a small off-grid woodland community that uses environmentally sound methods of working the land without using fossil fuels. Self-built houses have been granted planning on the condition that the community make a living from the land, mainly through forestry, apple work and gardening.

The land is about 28 acres of douglas fir, larch, and mixed broadleaf woodland, managed using horses, two person saws, and a wood-fired steam-powered sawmill. The pastures, orchards, and gardens are organically certified, worked using a combination of no-dig methods and horse-ploughing. Apple juice and cider are pressed for sale, along with the preparation of preserves, most vegetables are grown on site, along with keeping chickens, bees, and a milking cow .

Water is available to drink from a spring, by which the settlement is named, most of daily life is outside, electricity is provided via a 12 volt system and toilets are compost toilets. Wood is burned for cooking, heating, and hot water in a bath house, in general clothes are washed by hand. The community is made up of 6 adults, plus long-term volunteers, meat from site is eaten during months where other stocks of food ar less available and there is no particular shared spirituality.

This text is based on text from the tinker's bubble website here: http://www.tinkersbubble.org/index.php

[edit] The community of Scoraig

Scoraig is a scattered, off-grid community of about 70 people, it has no roads, with access to the nearest one only reachable by crossing Little Loch Broom, most residents have their own boat. On frequent stormy days it is too rough to make the trip, so a path leads 5 miles up the coast to scarcely less-remote Badrallach further along the peninsula.

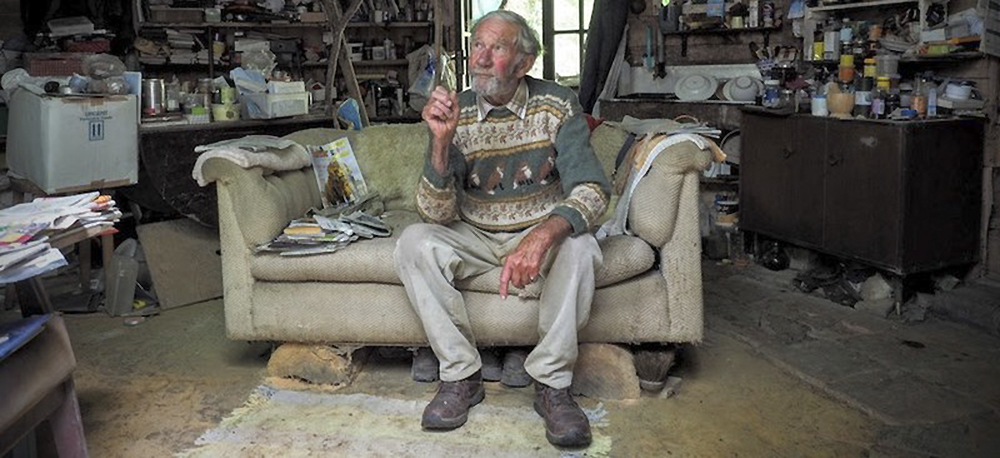

The residents of Scoraig live in relative isolation, partly powering their homes and school with wind power. Among the inhabitants are crofters with cattle and sheep, a violin maker, a wind power expert, a Russian translator, volunteers and a part-time postal worker. Census records show that in 1871 say there was over 380 people in the area, all Gaelic speakers, by the 1960's the last residents had left, only to see a new generation of residents move there a decade later. In around 1975 some of the earliest new generation of tenants moved to Scoraig, with electricity via a wind turbine made by a resident coming some few years later. In 2018 the BBC wrote a short photo piece about some of the residents of Scoraig; The remote UK community living off-grid.

[edit] Lammas Eco Village

Lammas Eco Village in Wales is a well-known example of an eco village in the UK. Located in Pembrokeshire, Wales, it consists of nine smallholdings and around 75 people. The community received some initial funding from the UK Department of Energy and Climate Change in order to explore low-impact, affordable, and climate-friendly living, where residents practice sustainable agriculture and live in low-impact dwellings.

The village aims to be self-reliant in terms of energy, food, and other resources. Water, trackways and electricity are managed collectively and the plots are largely dedicated to growing food, land-based businesses, growing biomass and processing organic waste. Land-based enterprises include fruit and vegetable production, livestock and bees, woodland and willow crafts, value-added food production, and seed production.

Residents use combinations of hydro power, solar power and wind turbines. The Tir y Gafel residents benefit from a shared 27kW hydro generator, heating is generally supplied from either electrical dump loads (converting spare electricity into heat) or timber (either waste timber from woodland management or from short-rotation-coppice biomass plantations).

[edit] Hockerton Housing Project

Hockerton Housing Project is an off-grid eco housing development located in Hockerton, Nottinghamshire, England. It serves as an example of sustainable and low-impact living and was initiated by a group of five families who aimed to create an environmentally friendly community that operates off-grid, producing its own energy and managing resources in a sustainable manner, it was set up and planning received on the basis of being a small holding.

A linear cluster of five self-sufficient houses built in Nottinghamshire in 1997 by Brenda Vale, the building are earth bermed, that is that certain parts of the building are left insulation free allowing the earth that surrounds the building help regulate the temperature, known as earth coupling. The houses in Nottingham require minimal heating and have lower-than-normal energy consumption, supplied by onsite renewable energy generation from two 6 kW turbines and 7.6 kW solar panels.

The community also has a working reed bed system, which is able to clean the waste water via a series of different organic pools, gradually becoming cleaning as the waste moves through the system, which is incorporated into the landscape surrounding the buildings.

[edit] Other examples

There are a number of other examples of communities which were either initially off grid and later joined the grid due to growth or maintain an electrical connection to the National Grid but produce a large proportion of their energy on site, whilst also managing waste water systems off grid. Many of these have developed into cultural and educational centres as well as standing examples of alternative and sustainable approaches to community developments, visited by many thousands of interested individuals each year.

[edit] The Centre for Alternative Technology

The Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT) was founded in 1973 by Gerard Morgan-Grenvilleon, with a 20,000 pound donation, on a disused slate quarry in Mid Wales. It began as an off-grid community, experimenting with alternative types of technology in response to the 1970s oil crisis and a growing concern about the environmental impact of fossil fuels. The year 2023 is therefore a milestone 50 year since it was established. It has evolved from a community to a visitor centre to an educational charity specialising in sharing practical solutions for sustainability.

[edit] Findhorn Foundation

Findhorn Foundation, Scotland: While not entirely off-grid, the Findhorn community Scotland was founded by three people, Peter and Eileen Caddy and Dorothy Maclean unintentionally in 1962. It was formally registered as a Scottish Charity called the Findhorn Foundation in 1972, purchasing the nearby Cluny Hill Hotel in 1975 and the local caravan park in 1983, whereby its membership had grown to around 300.

Towards the end of the 1980s, Findhorn began to develop its Ecovillage Project, including a variety of low impact housing, three wind turbines and a pioneering biological sewage treatment plant, called The Living Machine, which was the first to be constructed in Europe.

In 1995 the Findhorn community and the evolving informal ecovillage network organised a conference at Findhorn: Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities for the 21st Century. From this initiative the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN) was established, with the Foundation becoming one of its founding members.

As such the community, although now not disconnected to the grid, it has a long history and well-known as a community focused on ecological sustainability and spiritual growth, incorporating off grid renewable energy sources and wase water treatment.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Bedzed.

- Building Transformation: concepts and definitions.

- Circular Construction in Regenerative Cities (CIRCuIT).

- Circular economy.

- CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme.

- Design life.

- Earth overshoot day.

- Ecological impact assessment.

- Economic sustainability.

- Life.

- Product-life extension: product-life factor.

- Reduce, reuse, recycle.

- Regenerative design.

- Sustainable materials.

- Sustainable procurement.

- The sustainability of construction works.

Featured articles and news

HBPT and BEAMS Jubilees. Book review.

Does the first Labour budget deliver for the built environment?

What does the UK Budget mean for electrical contractors?

Mixed response as business pays, are there silver linings?

A brownfield housing boost for Liverpool

A 56 million investment from Homes England now approved.

Fostering a future-ready workforce through collaboration

Collaborative Futures: Competence, Capability and Capacity, published and available for download.

Considerate Constructors Scheme acquires Building A Safer Future

Acquisition defines a new era for safety in construction.

AT Awards evening 2024; the winners and finalists

Recognising professionals with outstanding achievements.

Reactions to the Autumn Budget announcement

And key elements of the quoted budget to rebuild Britain.

Chancellor of the Exchequer delivers Budget

Repairing, fixing, rebuilding, protecting and strengthening.

Expectation management in building design

Interest, management, occupant satisfaction and the performance gap.

Connecting conservation research and practice with IHBC

State of the art heritage research & practice and guidance.

Innovative Silica Safety Toolkit

Receives funding boost in memory of construction visionary.

Gentle density and the current context of planning changes

How should designers deliver it now as it appears in NPPF.

Sustainable Futures. Redefining Retrofit for Net Zero Living

More speakers confirmed for BSRIA Briefing 2024.

Making the most of urban land: Brownfield Passports

Policy paper in brief with industry responses welcomed.

The boundaries and networks of the Magonsæte.